Opera isn’t just singing in beautiful costumes. It’s a living organism where every sound has its own DNA. But how do you understand this complex world without losing yourself in the labyrinth of arias and recitatives?

First secret: forget about “proper” listening. Many believe you should study the libretto in advance. Nonsense! The best approach is to come as a “blank slate.” Remember Janáček’s opera “From the House of the Dead”? Even experts argue about its meaning. Just listen with your heart.

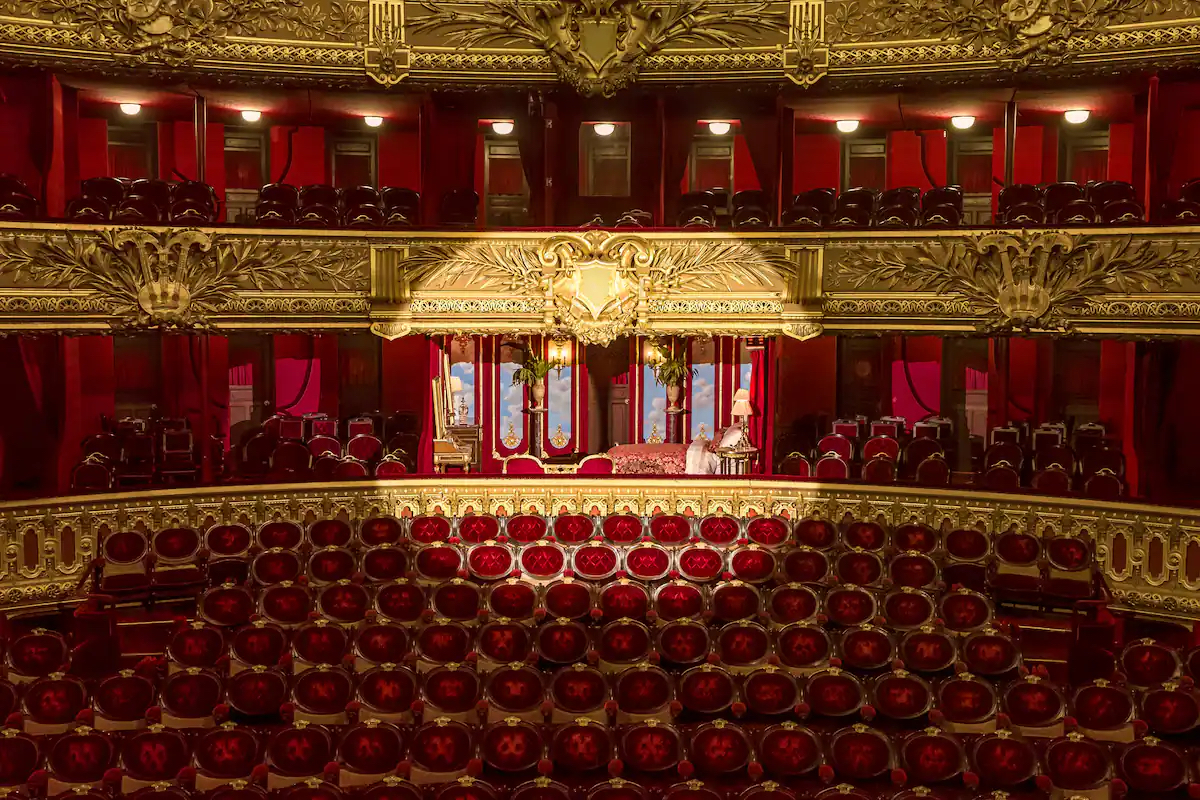

Imagine: you’re sitting in the hall, and suddenly… silence. Not the silence when everyone is quiet, but the kind that sounds. Opera has the concept of “Puccini’s pauses”—moments when the composer deliberately stops time. These seconds are worth more than entire arias.

Books are your secret ally. Not operatic ones, but ordinary ones! Reading “War and Peace,” you develop the same ability to follow multiple plot lines that’s necessary in Wagner’s “Ring of the Nibelung.” Detective stories teach you to hear leitmotifs—musical “clues” that the composer scatters throughout the score.

Here’s the paradox: to understand Berg’s “Lulu”—an opera without conventional melody—you need to read poetry! Not classical, but avant-garde. Khlebnikov, Kruchenykh. Their sound experiments will teach your ear to perceive “ugly” sounds as beauty.

Pay attention to what others don’t notice. Singers’ breathing between phrases. The rustling of pages in the orchestra pit—yes, sometimes it’s audible! Coughing in the hall—it’s also part of the performance. Japanese theater has the concept of “ma”—meaningful pause. Opera has thousands of such “ma.”

Opponents will say: “This is all nonsense, opera is elitist art!” And I’ll respond: I’ve seen the strongest emotions from opera in children. A five-year-old cries during “Madame Butterfly,” understanding not a word in Italian. Why? Because they weren’t taught what they can and cannot feel.

Read fairy tales aloud—this is preparation for opera. When you change your voice for different characters, you’re doing the same thing an opera singer does: creating character through voice. “Little Red Riding Hood” in your performance is a mini-opera for a home audience.

Strange but true: modern neuroscience research shows that people who read to children from birth better perceive complex music. The brain becomes accustomed to multilayering: parent’s voice, rustling pages, own emotions. This is preparation for symphonic thinking.

Don’t be afraid to fall asleep during opera. Mahler said his music should contain the whole world. Sometimes this world is so vast that consciousness switches off. This is normal! The subconscious continues working, absorbing harmonies and rhythms.

Ultimately, opera is the art of time. And time is best understood through stories. Therefore, read! Read to children, read yourself, read aloud. Every fairy tale read is a rehearsal before the great operatic performance of life. And who knows, perhaps it’s in a children’s book that you’ll find the key to understanding “Parsifal” or discover that “Thumbelina” and “La Traviata” are the same story about finding one’s place in the world.