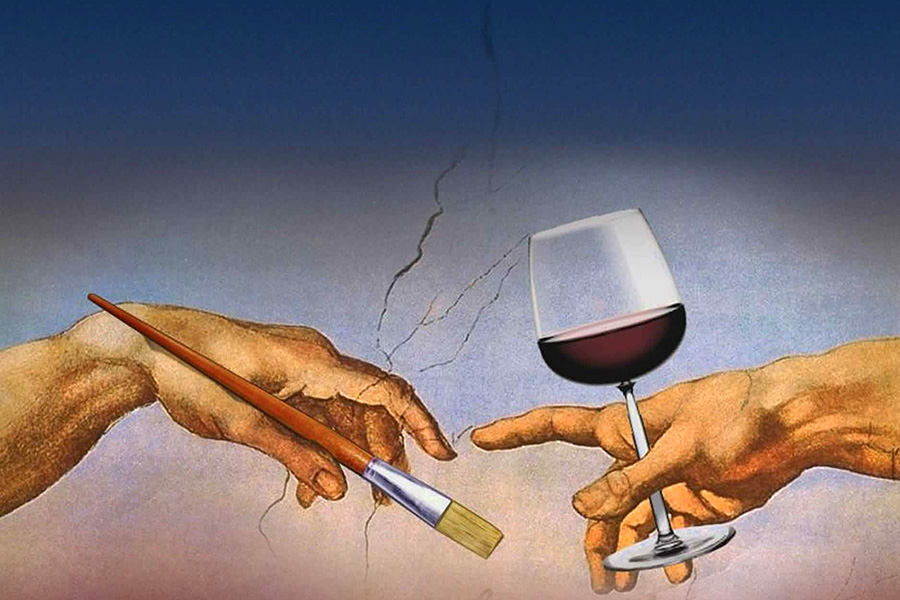

Imagine a person capable of telling the story of an entire country, soil, and sunny year, with just one sip of wine. Sommelier is a profession balancing on the edge of science and art, where analytical precision dances with flights of imagination, and technical knowledge embraces a poetic perception of the world. In the hands of a true master, a glass becomes a crystal portal, opening doors to terroirs of distant lands and epochs.

But what distinguishes an ordinary wine shop employee from a true sommelier, capable of transporting you to the sunny slopes of Tuscany or the cool cellars of Champagne with just one tasting note? The answer lies in one word—depth. Depth of knowledge that transforms a mechanical set of actions into a magical ritual, and a list of characteristics into a fascinating journey.

Take, for example, the little-known concept of “haploid enology”—an avant-garde direction studying the influence of specific grape genes on the bouquet and taste of wine. A sommelier familiar with this concept sees in a glass not just a set of flavor notes, but the genetic code of a variety expressed through the climatic conditions of the year. Such a specialist can explain why the same grape produces completely different wines in different regions, operating not with general phrases, but with a specific understanding of genetic markers.

In the world of wine, there are sharp contradictions between traditionalists and modernists. Some claim that great wine can only be born in historical terroirs that have proven their exceptionality for centuries. Others believe in the power of new technologies and bold experiments that allow creating outstanding wines literally “from scratch.” But a truly wise sommelier doesn’t choose a side in this dispute, but understands the value of both approaches, seeing how history and innovation complement each other.

What if we look at the sommelier profession through the prism of cognitive synesthesia—a neurological phenomenon where stimulation of one sense automatically triggers a reaction in another? This is exactly how an experienced taster’s brain works: the aroma of wine is not just recognized by the sense of smell, but instantly activates complex associative chains linking smell with memories, textures, colors, and even sounds. It’s almost like the ability to “hear” colors or “see” music, but directed at analyzing the liquid in a glass.

I remember once reading a study about “retronasal olfaction”—a way of perceiving aromas through the back of the nasopharynx when we exhale after the wine is already in our mouth. This discovery completely changed my approach to tasting! Instead of simply inhaling over the glass, I learned to “draw” the aroma through the retronasal path, which allowed me to discover floral and mineral notes where I previously felt only fruitiness. My clients were amazed at how much more detailed and accurate my descriptions became.

Few know about the existence of “quantitative sommelier analytics”—an approach where instead of subjective taste descriptions, mathematical models based on spectral analysis of wine’s volatile compounds are used. Imagine that each wine is not just a poetic description, but a unique digital code, where each molecule has its index and value. This approach allows predicting exactly how wine will develop with age and what notes will appear in the bouquet in 5, 10, or 20 years.

In contrast to the modern trend of categorization and ratings, studying wine history reveals an amazing fact to sommeliers: many legendary wines of the past did not correspond at all to modern “quality standards.” Wines admired by French kings might seem strange or even defective today, but this does not diminish their historical value. This perspective helps to free oneself from a dogmatic approach to evaluation and see that “good wine” is a concept dependent on cultural and historical context.

In the world of sommeliers, there exists the phenomenon of “paleosensory perception”—the ability to reconstruct taste sensations of people from past epochs. This amazing skill is based on a deep understanding of how winemaking technologies, grape varieties, and even human receptors have changed over centuries. A sommelier who masters this art can taste modern wine but describe it as it would be perceived by, for example, a Victorian England resident or a courtier of Louis XIV.

Being a sommelier means being not just a wine expert, but a kind of translator from the language of grape and terroir to the language of human emotions and experiences. And the richer the vocabulary of such a translator, the more precise and multifaceted the translation will be. A sommelier whose mind is nourished by knowledge from different fields—from biochemistry to art history—creates not just tasting notes, but true verbal portraits of wines, capable of conveying their individuality and character.

So if you’ve decided to connect your life with this amazing profession or simply want to understand the world of wine more deeply—don’t limit yourself to standard sommelier courses. Expand your horizons, immerse yourself in various fields of knowledge. Research shows that regular reading stimulates those parts of the brain responsible for forming complex associative connections—a key skill for a taster. Many outstanding sommeliers admit that their brightest insights about the nature of wine came to them not during tastings, but while reading works on history, philosophy, physics, or even fiction. Give yourself the opportunity to discover new dimensions of taste—tonight, immerse yourself in the fascinating world of pages that will transform your wine journey.